By Reginald Thistlewhite, Historical Correspondent

For twelve days in the year 812, the fate of the Kingdom hinged on a single gate. The northern entrance to Inverness, then a modest stone arch defended by a handful of guards, became the focus of a siege that tested both the strength of the city walls and the resolve of its citizens.

The attackers were the forces of Lord Ethelmar of Brambleford, who, embittered by his exclusion from the royal council, marched upon the capital with nearly two thousand men. His intent was simple: seize Inverness, dethrone the young King Athelred, and proclaim himself regent. Yet the city’s defenders numbered fewer than three hundred, most of them tradesmen hastily pressed into service.

Chroniclers of the time record that the gate was fortified with carts overturned and chained, barrels of stone stacked high, and cauldrons of pitch prepared to pour down on any who attempted to batter the doors. Women and children carried water, fetched arrows, and even stood upon the walls to jeer at the besiegers. “It was as though the entire city had become one body,” wrote Brother Cadwyn in his Chronicle of the Year.

On the third day, Ethelmar ordered his men to storm the gate. Ladders clattered against the walls, and the sound of axes on timber rang out. Yet the defenders held firm. A baker named Osric, according to legend, hurled loaves of stale bread upon the enemy when stones ran short, earning laughter even amid the din of battle.

The siege dragged on. Supplies in the city dwindled. Rats became part of the diet, and one account claims that parchment itself was boiled into broth. But morale held, sustained by the certainty that relief must come. That relief arrived on the twelfth day, when loyalist forces under Earl Theobald swept down from the west. Caught between defenders and rescuers, Ethelmar’s men broke. The rebel lord was captured and later executed; his rebellion extinguished at the very gate he had sworn to claim.

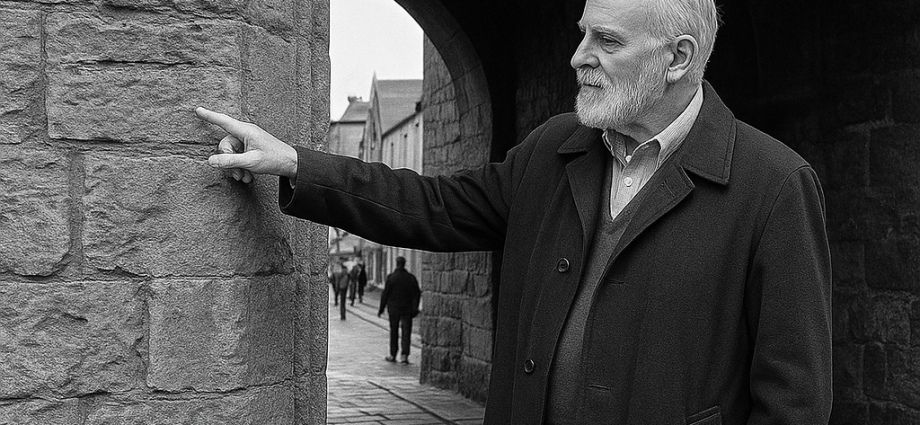

Inverness Gate itself, though battered, survived. Rebuilt and expanded in later centuries, it remains to this day a symbol of the city’s endurance. Its weathered stones still bear the scars of axe and fire, though few passersby pause to notice.

Modern historians debate the true significance of the siege. Some argue that it was little more than a skirmish inflated into legend. Others insist that without those twelve days of resistance, the Kingdom might well have fractured. What is certain is that the story has endured, passed from chroniclers to schoolchildren, from mural to memory, until Inverness Gate stands not merely as an entryway, but as a monument.

As historian Elijah Marcombe notes, “The gate is not grand, not like the castles or cathedrals. But it is ours. Ordinary people defended it, and in doing so, they defended us all. It is the closest thing we have to a people’s victory.”

Today, Inverness bustles beyond recognition from the city of 812. Yet the gate remains. Tourists photograph its arch, unaware that their feet tread ground once stained with blood. Locals hurry through on their way to market, seldom pausing to look up. But for those who remember, the stones whisper: here the Kingdom endured.