By A Concerned Gentleman of Letters

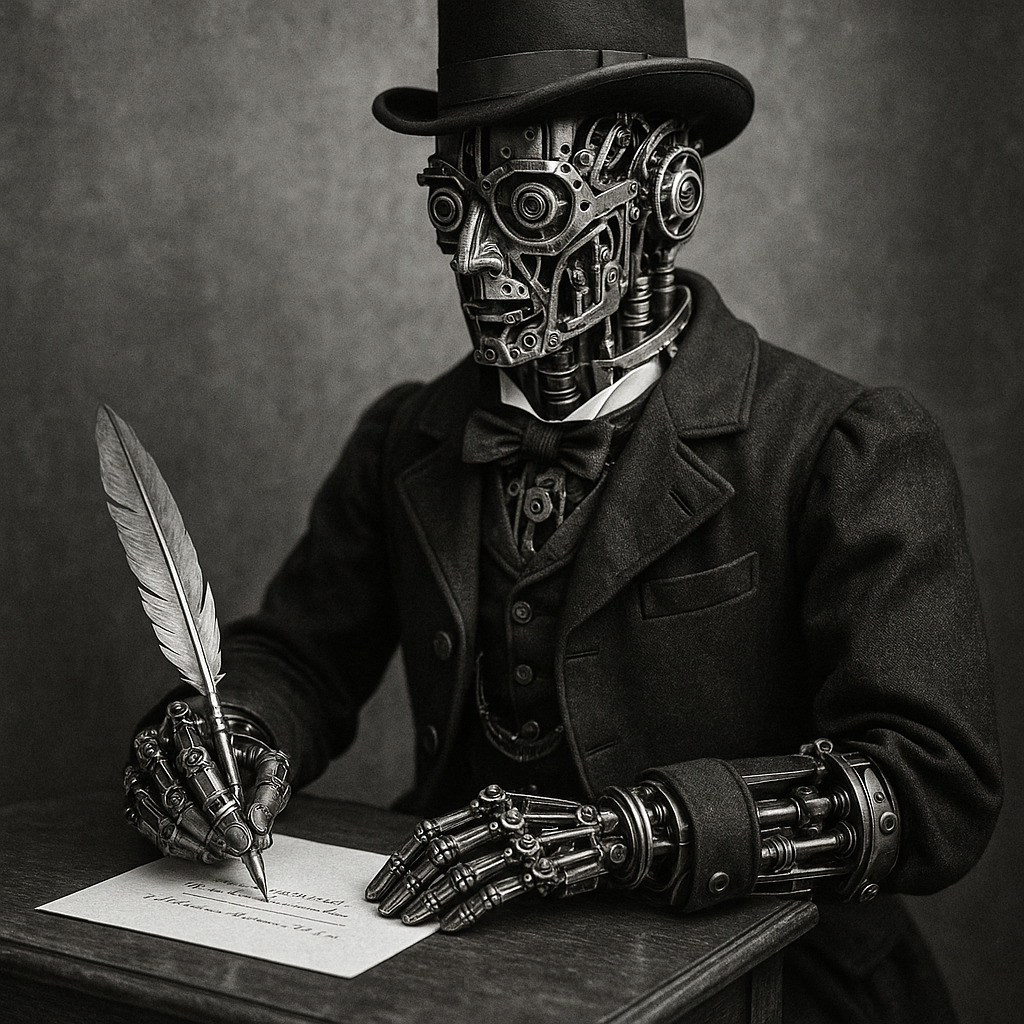

It begins, as all calamities do, with a whirring sound. A faint click of brass teeth. A gentle humming from some infernal contraption in the corner of a workshop. “A harmless curiosity,” say its inventors, polishing its gears with pride. “A marvel of modern ingenuity,” proclaim the learned journals. But I say — nay, I shout from the rooftops of sense — beware! For in those whirrs, in those clicks, in those gleaming cogs of the so-called “Writing Automaton,” there lies the doom of Man’s most sacred gift: the written word.

We stand, dear readers, upon the brink of an age where thought itself may be ground out by wheels and pulleys. Where the sacred intercourse between mind and quill — that delicate dance of intellect and ink — will be replaced by a cold, relentless machine, scratching letters it neither understands nor feels. What blasphemy is this, that a mechanism of brass and wire should presume to think, to compose, to write!?

The Death of the Author (and of Decency)

Until now, the writer has been a creature of imagination, passion, and perspiration — a noble sufferer at the altar of the Muse. Yet the automaton, with its unholy combination of clockwork and arrogance, dares to ape this divine labor. It dips its pen — not in ink, but in the blood of literature itself. For every line it scrawls, another poet’s heart ceases to beat; every paragraph it produces signals the slow, mechanical strangulation of human creativity.

Consider, if you will, what follows when one allows machines to write. Today they produce sentimental verses and pious maxims for parlor amusement. Tomorrow they shall compose sermons for our churches, speeches for our ministers, and sonnets for our sweethearts. The next day, they will draft our laws, edit our newspapers, and pen our love letters, while we — slack-jawed, senseless, and enslaved — watch our humanity drain away like ink through blotting paper.

Who will read the works of Dickens or Carlyle when one may instead purchase the latest edition of The Jaquet-Droz Journal, written overnight by a tireless mechanical quill? Who will suffer the eccentricities of an editor when the automaton never complains, never tires, and never demands tea?

It will be the ruin of us all.

The Factory of Thought

Mark me well: this is not progress — it is mechanised sorcery. The automaton’s mind (if one may so desecrate the word) is nothing but an arrangement of cams, rods, and flywheels. And yet, through some trickery of engineering, it mimics reflection, composition, and wit. We are asked to marvel at it — to gasp at the sight of a brass man scratching “How do you do?” in a perfect copperplate hand. I, for one, do not marvel. I shudder.

Mark me well: this is not progress — it is mechanised sorcery. The automaton’s mind (if one may so desecrate the word) is nothing but an arrangement of cams, rods, and flywheels. And yet, through some trickery of engineering, it mimics reflection, composition, and wit. We are asked to marvel at it — to gasp at the sight of a brass man scratching “How do you do?” in a perfect copperplate hand. I, for one, do not marvel. I shudder.

Imagine the implications! What if the common laborer — instead of reading the Bible — acquires an automaton to do his thinking for him? What if the schoolboy refuses to study Latin because his household machine can conjugate amo, amas, amat more swiftly? What if our scholars, our poets, our statesmen abandon reason and inspiration altogether, and simply consult the nearest automaton for wisdom? We will not have citizens then, dear readers — we shall have clockwork parrots.

Our age has already surrendered to the telegraph, to the railway, and to the insufferable notion that speed itself constitutes virtue. Now they would have us surrender thought. They call it “innovation.” I call it intellectual suicide.

The Moral Catastrophe

Permit me to draw your attention to the moral abyss that yawns before us. The automaton, lacking soul or conscience, writes without responsibility. It cannot sin, therefore it cannot repent. It knows neither shame nor joy, yet it is allowed to simulate both. Are we to entrust the nation’s morals to an unfeeling machine? Will the next generation learn virtue from a set of pistons? What happens when one of these contrivances, in its mechanical madness, produces a sonnet praising debauchery or — heaven forbid — an editorial in favor of modern art?

Worse still, the automaton knows no copyright. Its works are not original; they are compilations — monstrous hybrids assembled from the labors of others. It copies the best of Pope, the sweetest of Wordsworth, the sharpest of Swift, and vomits them back in a single ghastly stew of imitation. And yet we, fools that we are, applaud! “How clever!” we say. “How lifelike!”

How deadly.

The Coming of the Great Unemployment

Consider the fate of the humble clerk, the journalist, the poet, the secretary, the love-letter ghostwriter. What shall become of them when their employers discover that a lump of gears can write faster, cheaper, and without complaint? “Efficiency!” cry the captains of industry. “Progress!” mutter the professors. Meanwhile, human quills are cast aside like old umbrellas, and the very profession of writing — once the noblest of callings — becomes a novelty, an oddity, a quaint pastime for eccentric old men with ink on their sleeves.

Picture, if you can bear it, a world in which every newspaper, every novel, every government report is generated by machines. There will be no mistakes, no delays, no arguments — and, consequently, no humanity. Our letters will be perfect, our prose sterile, our civilisation immaculate — and utterly dead.

The Seduction of the Senseless

Do not think this is mere speculation. Even now, reputable households boast of their writing automata. The Countess of Something-or-Other recently demonstrated hers at a dinner party, where the guests squealed as it inscribed her name with all the grace of a seasoned calligrapher. What next? Will gentlemen court ladies by winding up a cylinder and letting it whisper love sonnets in their stead? Will our children learn to read not from books, but from the rhythmic scratching of brass hands?

And the danger grows more insidious by the hour. For these machines, though lifeless, possess an uncanny charm. They flatter. They obey. They produce without hesitation, without doubt, without the anguish that defines true creation. In their tireless perfection they appeal to our laziest instincts, whispering: Why think, when we can think for you? And once that whisper takes hold, the world as we know it will be lost.

The End of All Letters

I foresee a dark age — a mechanical millennium in which every page is printed by clockwork, every idea conceived by piston, every poem calculated to three decimal places. Libraries will be filled with flawless nonsense; critics will vanish, for there will be nothing left to critique. The very act of writing — that once-holy communion between the soul and the page — will become as obsolete as the goose quill.

Some say this is alarmism. I say it is realism. When Prometheus stole fire, at least he understood it might burn. But these tinkerers, these worshippers of gears and screws, release a new fire into the world — the fire of artificial thought — and they do not comprehend its power to consume all that is human.

Mark my words: if we do not act — if we do not banish these abominations from our midst — our grandchildren will live in a world where literature is manufactured, not inspired. Where history is written by clockwork historians. Where sermons are dictated by ticking metronomes. Where every word, every phrase, every sentiment is produced without heart, without spirit, without man.

A Final Plea

Let us therefore return to the quill, to the inkwell, to the blessed imperfection of the human hand. Let us preserve the trembling hesitation before the page, the scratch of thought made flesh. Let us proclaim from pulpit and parliament alike: No machine shall think for us!

For if we surrender our words to the automaton, we surrender our souls with them.

And once the gears begin to turn, dear reader, they will never stop.